Summary

Current: US Representative of WA District 5 since 2005

Affiliation: Republican

Leadership: Chair, Committee on Energy and Commerce

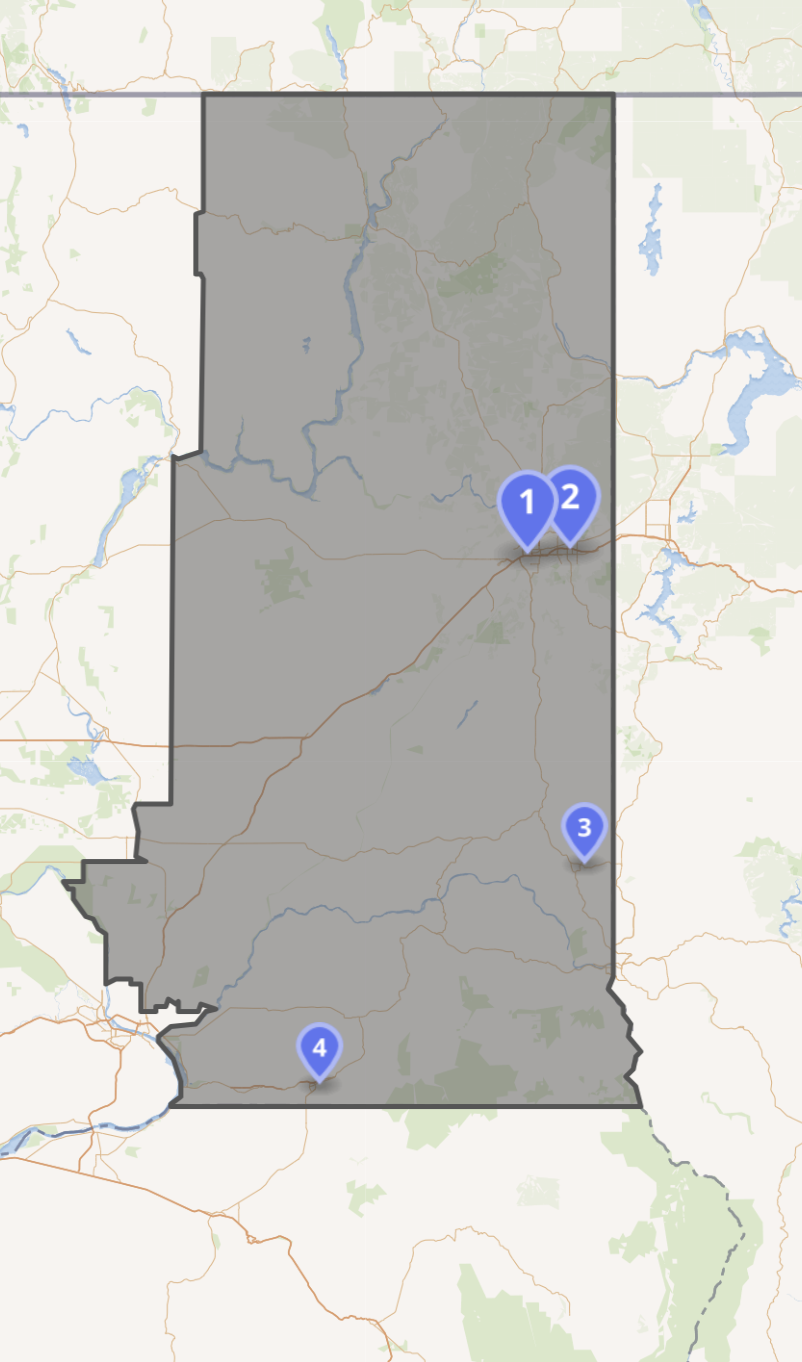

District: Eastern Washington counties of Ferry, Stevens, Pend Oreille, Lincoln, Spokane, Whitman, Walla Walla, Columbia, Garfield, and Asotin, along with parts of Adams and Franklin. It is centered on Spokane.

Next Election:

History: McMorris Rodgers earned an Executive MBA from the University of Washington in 2002.

McMorris Rodgers previously served in the Washington House of Representatives. From 2013 to 2019, she chaired the House Republican Conference. She gained national attention in 2014, when she delivered the Republican response to President Barack Obama’s 2014 State of the Union Address.

Featured Quote: Big Tech has broken my trust. They’ve failed to promote free speech & they censor political viewpoints they disagree with. But, do you know what has convinced me Big Tech is a destructive force? It’s how they’ve abused their power to manipulate and harm our children.

Featured Video: GOP Lawmakers seek NIH records on research funding, COVID-19 origins

OnAir Post: Cathy McMorris Rodgers WA-05

News

About

Source: Government page

Cathy McMorris Rodgers is Eastern Washington’s chief advocate in Congress and a rising star in American politics. Since first being elected to the House in 2004, she has earned the trust of her constituents and praise on Capitol Hill for her hard work, conservative principles, bipartisan outreach, and leadership to get results for Eastern Washington. As someone who grew up on an orchard and fruit stand in Kettle Falls, Washington, worked at her family’s small business, and later became a wife and working mom of three, Cathy has lived the American Dream, and she works every day to rebuild that Dream for our children and grandchildren.

Cathy McMorris Rodgers is Eastern Washington’s chief advocate in Congress and a rising star in American politics. Since first being elected to the House in 2004, she has earned the trust of her constituents and praise on Capitol Hill for her hard work, conservative principles, bipartisan outreach, and leadership to get results for Eastern Washington. As someone who grew up on an orchard and fruit stand in Kettle Falls, Washington, worked at her family’s small business, and later became a wife and working mom of three, Cathy has lived the American Dream, and she works every day to rebuild that Dream for our children and grandchildren.

Cathy served as Chair of the House Republican Conference from 2012 to 2018. Cathy was the 200th woman ever elected to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives and the first woman to give birth three times while in office.

Since being elected to Congress in 2004, Cathy has focused on moving legislation based on the priorities she hears in conversations with the people of Eastern Washington. Her mission is to restore trust and confidence in representative government and the rule of law, and lead as a trust-builder, ability-advocate, and unifying force to get results for hardworking men and women in Eastern Washington.

Personal

Full Name: Cathy Anne McMorris Rodgers

Gender: Female

Family: Husband: Brian; 3 Children: Cole, Grace, Brynn

Birth Date: 05/22/1969

Birth Place: Salem, OR

Home City: Kettle Falls, WA

Religion: Christian

Source: Vote Smart

Education

MBA, University of Washington, 1999-2002

BA, Pre-Law, Pensacola Christian College, 1986-1990

Political Experience

Representative, United States House of Representatives, Washington, District 5, 2005-present

Member, Republican Whip Team, United States House of Representatives

Chair, Majority Conference, United States House of Representatives, 2012-2019

Vice Chair, House Republican Conference, 2008-2012

Representative, Washington State House of Representatives, 1994-2004

Minority Leader, Washington State House of Representatives, 2002-2003

Professional Experience

Former Employee, Peachcrest Fruit Basket

Former Campaign Manager/Legislative Aide, Washington State Legislator Bob Morton

Offices

Colville

555 South Main Street, Suite C

Colville, WA 99114

Phone: 509-684-348

1

Spokane

10 North Post Street, Suite 625

Spokane, WA 99201

Phone: 509-353-2374

Walla Walla

26 E. Main Street, Suite 2

Walla Walla, WA 99362

Phone: 509-529-9358

Washington, D.C.

1035 Longworth House Office Building

Washington, D.C. 20515

Phone: 202-225-2006

Contact

Email: Government

Web Links

Politics

Source: none

Election Results

To learn more, go to this wikipedia section in this post.

Finances

Source: Open Secrets

Committees

Caucuses

New Legislation

Issues

Economy & Jobs

Agriculture

As a native of one of the most agriculture-intensive districts in the country, Cathy has long been a champion for Eastern Washington’s farmers. Cathy continues to protect crop insurance from deep cuts, open new trade markets for farmers through trade and market access programs, and support robust funding for agriculture research like the transformative work at Washington State University. Cathy has also been a driving force in Congress to help provide wheat growers relief from low falling numbers, including developing a long-term plan to more accurately measure wheat quality, fixing the grain glitch, and encouraging smart trade policies that put farmers first.

Energy & Environment

Hydropower

As co-chair of the Northwest Energy Caucus and the founder of the Hydropower Caucus, Cathy is a long-time champion of dams and hydropower as a source of renewable, clean, reliable, affordable energy. In 2017, Cathy passed her Hydropower Policy Modernization Act through the House to modernize and streamline the hydropower relicensing process and encourage the development and investment in clean, renewable hydroelectric energy. In the Spring of 2018, Cathy also saw her legislation to protect the Columbia and Snake River dams pass the House, which stops the unnecessary and costly court-ordered spill and allows local experts and scientists to move forward with fish recovery efforts.

Forestry

The environment and the outdoors are a way of life in the Pacific Northwest, and Cathy is committed to environmental stewardship. That’s why in the Spring of 2018, she helped usher permanent forest management reforms into law that will keep our forests healthy and reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire. She also led in fixing “fire borrowing” at the U.S. Forest Service to correct budgetary issues at the Forest Service and ensure they have the resources to fight fires when they do happen.

In the Spring of 2018, Cathy ushered her bill into law to extend the Secure Rural Schools program which provides funding for rural, timber-dependent counties to fund public and municipal needs like infrastructure, public schools, law enforcement and more.

Cathy was instrumental in the development of the A to Z Project on the Colville National Forest and continues to advocate for local collaboration and public-private partnerships to get our forests working again and actively manage our vast natural resources. Cathy believes the A to Z Project should be a national model. She is also a strong supporter of carbon-neutral biomass as a clean, renewable energy resource.

Healthcare

In 2010, Cathy was appointed to the powerful House Energy and Commerce Committee – where almost half of all legislation pertaining to the economy must pass. She plays an active role in advancing affordable, patient-centered health care reforms. As co-chair of the Rural Health Caucus, she advocates for better access to affordable and quality health care services in our rural communities, and in early 2018, her legislation to extend and expand the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME) program was signed into law, which will help meet the doctor shortage in rural and underserved areas.

In 2015, Cathy’s Steve Gleason Act was signed into law to provide a temporary fix to a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) policy that limited access to speech-generating devices for people with ALS, like Spokane-native Steve Gleason, and other degenerative diseases. In 2018, Cathy’s Steve Gleason Enduring Voices Act was signed into law to make that fix permanent.

She is a longtime supporter of increased resources at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and has repeatedly voted for increases in funding to help combat the opioid epidemic in Eastern Washington and across the country.

As a co-sponsor, vocal advocate and co-author of the 21st Century Cures Act, Cathy played a key role in getting the bill passed in the House and signed into law. The legislation funds the discovery, development, and delivery of life-saving cures, and includes provisions that specifically benefit the people of Eastern Washington, such as funding for better rural health programs and support for Washington State University’s research on bacteria resistance to antibiotics. The bill was signed into law by President Obama in December 2016.

Governance

Federal Spending

Cathy believes that restoring trust and confidence in representative government starts with ensuring taxpayer dollars are used efficiently and effectively. In Spring of 2017, she introduced the Unauthorized Spending Accountability Act (USA Act), which requires greater scrutiny of federal spending by identifying government agencies and programs that are not authorized to receive funding and puts them on a path to sunset in three years unless Congress renews them. As McMorris Rodgers wrote in The Washington Post, “Every day, we hear Americans’ frustration about Washington’s seemingly unstoppable growth. For their sake, it’s time to force Congress to justify every taxpayer dollar it spends.” She has long supported a Balanced Budget Amendment and continues to work with her colleagues in Congress to bring reforms for the budget process so Congress can stop lurching from one funding crisis to the next.

Cathy is the co-chair of eight Congressional caucuses: Military Family, Down Syndrome, Lumber, Neuroscience, Hydropower, Northwest Energy, Rural Health Caucus, and the Mobility Air Forces Caucus.

In January 2014, McMorris Rodgers delivered the Republican address following the State of the Union, in which she articulated a hopeful, bold Republican vision that will make life better for the American people.

In 2006, Cathy married Brian Rodgers, a Spokane native and retired 26-year Navy Commander. In 2007, she gave birth to Cole Rodgers. Cole was born with Trisomy 21 and inspired Cathy to become a leader in the disabilities community. She has since welcomed two daughters into the world – Grace Blossom (December 2010) and Brynn Catherine (November 2013). She is the only Member of Congress in history to give birth three times while in office.

Human Rights

Disabilities

Cathy is a vocal, devoted champion for the disability community. In 2014, she played an instrumental role in securing final passage of the ABLE Act, which was described as the most comprehensive piece of disability legislation since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. This landmark legislation created tax-free savings accounts to empower individuals with disabilities to save and invest in their futures. To build on this success, she introduced and helped pass her ABLE to Work Act and ABLE Financial Planning Act, getting these pieces signed into law in December of 2017. These bills expand opportunities for people with disabilities by allowing them to explore work and save their earnings into their ABLE account without jeopardizing necessary benefits. Cathy believes that a job is so much more than a paycheck, it’s what gives each person dignity and purpose — the opportunity for a better life. She is dedicated to helping those with disabilities live their lives to the fullest.

Veterans and Military Families

A longtime advocate for members of the military and their families, Cathy co-founded the bipartisan Military Family Caucus with Rep. Sanford Bishop (D-GA) to provide military spouses and children a voice in Congress. She is also the co-chair of the Mobility Air Forces Caucus that advocates for the critical roles that air refueling, airlift and aero medical evacuation play in our national security. Eastern Washington is home to more than 68,000 veterans and Fairchild Air Force Base, which is why Cathy continues to be a vocal advocate in Congress for our veterans and military service members.

In August 2016, Cathy co-hosted the annual Military Family Summit at Fairchild Air Force Base with Caucus Co-Founder Representative Sanford Bishop (D-GA) to discuss the most pressing issues facing military families today — pay and benefits, community integration and transition, and the health and well-being of their families and children.

As a strong advocate for veterans, Cathy leads the charge in Congress to ensure our veterans have access to the best healthcare available. She believes the VA has lost sight of its mission to put veterans first. She has consistently voted to increase the budget of the VA, but she believes the VA has cultural and structural problems, not a funding problem, which is why she continually champions solutions to hold the VA accountable and improve how it works. Her Faster Care for Veterans Act, requires the VA to adopt technology that allows veterans to schedule appointments online. It was signed into law by President Obama in December 2016.

In 2017, Cathy introduced the Modernization of Medical Records Access for Veterans Act of 2017 to direct the VA Secretary to carry out a pilot program establishing a secure, patient-centered, portable medical records system to allow veterans access to their own comprehensive medical records. Also in 2017, she introduced the Ethical Patient Care for Veterans Act to require Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical professionals to report directly to state licensing boards if they witness unacceptable or unethical behavior from other medical professionals at the VA.

Cathy also led in returning the Spokane VA to 24-hour urgent care and partnering with the new medical school at Washington State University to work towards a teaching hospital designation for the Spokane VA, which will bring more residency slots and train doctors in our community.

More Information

Services

Source: Government page

District

Source: Wikipedia

Washington’s 5th congressional district encompasses the Eastern Washington counties of Ferry, Stevens, Pend Oreille, Lincoln, Spokane, Whitman, Walla Walla, Columbia, Garfield, and Asotin, along with parts of Adams and Franklin. It is centered on Spokane, the state’s second largest city.

Washington’s 5th congressional district encompasses the Eastern Washington counties of Ferry, Stevens, Pend Oreille, Lincoln, Spokane, Whitman, Walla Walla, Columbia, Garfield, and Asotin, along with parts of Adams and Franklin. It is centered on Spokane, the state’s second largest city.

Since 2005, the 5th district has been represented in the U.S. House of Representatives by Cathy McMorris Rodgers, a Republican. Rodgers’s predecessor, George Nethercutt, defeated Democrat Tom Foley, then Speaker of the House, in the 1994 elections; Foley had held the seat since 1965.

In presidential elections, the 5th district was once fairly competitive, but in recent years has generally been a safe bet for the Republicans. Although George W. Bush carried the district with 57% in 2000 and 2004, John McCain just narrowly won the district with 52% of the vote, while Barack Obama received 46% in 2008. In 2012, President Obama’s share of the vote dropped to 44%.

The first election in the 5th district was in 1914, won by Democrat Clarence Dill. Following the 1910 census, Washington gained two seats in the U.S. House, from three to five, but did not reapportion for the 1912 election. The two new seats were elected as statewide at-large, with each voter casting ballots for three congressional seats, their district and two at-large. After that election, the state was reapportioned to five districts for the 1914 election. The state’s 6th district was added after the 1930 census and first contested in the 1932 election.

District

Contents

Cathy Anne McMorris Rodgers (born May 22, 1969) is an American politician who served from 2005 to 2025 as the United States representative for Washington’s 5th congressional district, which encompasses the eastern third of the state and includes Spokane, the state’s second-largest city.[1][2] A Republican, McMorris Rodgers previously served in the Washington House of Representatives. From 2013 to 2019, she chaired the House Republican Conference.

McMorris Rodgers was appointed to the Washington House of Representatives in 1994. She became the minority leader in 2001. In 2004, she was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. She eventually became the highest-ranking Republican woman in Congress in 2009, when she ascended to leadership as vice chair of the House Republican Conference, and later, chair of the House Republican Conference. She gained national attention in 2014, when she delivered the Republican response to President Barack Obama‘s 2014 State of the Union Address.

In February 2024, she announced she would not seek reelection for the 2024 elections.[3] Republican Michael Baumgartner was elected to her seat and succeeded her in the 119th Congress.[4]

Early life and education

Cathy McMorris was born May 22, 1969, in Salem, Oregon, the daughter of Corrine (née Robinson) and Wayne McMorris.[5][6] Her family had come to the American West in the mid-19th century as pioneers along the Oregon Trail.[7][8] In 1974, when McMorris was five years old, her family moved to Hazelton, British Columbia, Canada. The family lived in a cabin while they built a log home on their farm.[5] In 1984, the McMorrises settled in Kettle Falls, Washington, and established the Peachcrest Fruit Basket Orchard and Fruit Stand. McMorris worked there for 13 years.[5][9]

In 1990, McMorris earned a bachelor’s degree in pre-law from Pensacola Christian College, a then-unaccredited Independent Baptist liberal arts college.[10][11] She earned an Executive MBA from the University of Washington in 2002.[12]

Career

Washington House of Representatives, 1994–2005

After completing her undergraduate education, McMorris was hired by state representative Bob Morton in 1991[13] as his campaign manager, and later as his legislative assistant.[14] She became a member of the state legislature when she was appointed to the Washington House of Representatives in 1994. Her appointment filled the vacancy caused by Morton’s appointment to the Washington State Senate.[14] After being sworn into office on January 11, 1994,[13] she represented the 7th Legislative District (parts or all of Ferry, Lincoln, Okanogan, Pend Oreille, Spokane, and Stevens Counties). She retained the seat in a 1994 special election.[15]

In 1997, she co-sponsored legislation to ban same-sex marriage in Washington State.[16][17]

In 2001, she blocked legislation “to replace all references to ‘Oriental’ in state documents with ‘Asian'”, explaining, “I’m very reluctant to continue to focus on setting up different definitions in statute related to the various minority groups. I’d really like to see us get beyond that.”[18]

She voted against a 2004 bill to add sexual orientation to the state’s anti-discrimination law, and was a vocal opponent of same-sex marriage.[5] She is credited for sponsoring legislation to require the state reimburse rural hospitals for the cost of serving Medicaid patients, and for her work overcoming opposition in her own caucus to pass a controversial gas tax used to fund transportation improvements.[19]

From 2002 to 2003, she served as House minority leader,[9] the top House Republican leadership post. She chaired the House Commerce and Labor Committee, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee, and the State Government Committee.[20] She stepped down as minority leader in 2003 after announcing her candidacy for Congress.[21] During her tenure in the legislature, she lived in Colville; she has since moved to Spokane.[citation needed]

U.S. House of Representatives

Elections

In 2004, McMorris ran for the United States House of Representatives in the 5th District; she already represented much of the district’s northern portion. She received 59.7%[22] of the vote for an open seat, defeating the Democratic nominee, hotel magnate Don Barbieri. The seat had become vacant when five-term incumbent George Nethercutt retired to run for the U.S. Senate.

Tenure

McMorris Rodgers is a member of the Republican Main Street Partnership,[23] the Congressional Constitution Caucus,[24] and the Congressional Western Caucus.[25]

In November 2006, McMorris Rodgers was reelected with 56.4% of the vote, to Democratic nominee Peter J. Goldmark‘s 43.6%.[26] In 2007, she became the Republican co-chair of the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues, which pushed for pay equity, tougher child support enforcement, women’s health programs, and laws protecting victims of domestic violence and sexual assault.[27]

In 2008, McMorris Rodgers received 211,305 votes (65.28%), to Democratic nominee Mark Mays’s 112,382 votes (34.72%).[28] On November 19, 2008, she was elected to serve as vice chair of the House Republican Conference for the 111th United States Congress, making her the fourth-highest-ranking Republican in her caucus leadership (after John Boehner, Minority Whip Eric Cantor, and conference chair Mike Pence) and the highest-ranking Republican woman.[29] In 2009, she became vice chair of the House Republican Conference,[30] and served until 2012, when she was succeeded by Lynn Jenkins.[31]

McMorris Rodgers won the 2010 general election with 150,681 votes (64%), to Democratic nominee Daryl Romeyn’s 85,686 (36%).[32] Romeyn spent only $2,320, against McMorris Rodgers’s $1,453,240.[33] On November 14, 2012, she defeated Representative Tom Price to become chair of the House Republican Conference.[34]

In the 2012 general election, McMorris Rodgers defeated Democratic nominee Rich Cowan, 191,066 votes (61.9%) to 117,512 (38.9%).[35]

McMorris Rodgers sponsored legislation that would speed the licensing process for dams and promote energy production. According to a Department of Energy study, retrofitting the largest 100 dams in the country could produce enough power for an additional 3.2 million homes. The legislation reached President Obama’s desk without a single dissenter on Capitol Hill.[36]

In January 2014, it was announced that McMorris Rodgers would give the Republican response to President Barack Obama‘s 2014 State of the Union Address. House speaker John Boehner and Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell made the decision.[37][38] McMorris Rodgers is the 12th woman to give the response,[39] and the fifth female Republican, but only the third Republican to do so alone, after New Jersey governor Christine Todd Whitman in 1995[40] and the Spanish response by Florida representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, the most senior female Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives, in 2011. Ros-Lehtinen also gave the Spanish response that year, which was largely a translation of McMorris Rogers’ remarks.[41]

In 2014, the Office of Congressional Ethics recommended that the United States House Committee on Ethics initiate a probe into allegations by a former McMorris Rodgers staff member that McMorris Rodgers had improperly mixed campaign money and official funds to help win the 2012 GOP leadership race against Price. McMorris Rodgers denied the allegations.[42] In September 2015, Brett O’Donnell, who worked for McMorris Rodgers, pleaded guilty to lying to House ethics investigators about how much campaign work he did while being paid by lawmakers’ office accounts, becoming the first person to be convicted of lying to the House Office of Congressional Ethics.[43] The OCE found that McMorris Rodgers improperly used campaign funds to pay O’Donnell for help in her congressional office, and improperly held a debate prep session in her congressional office. A lawyer for McMorris Rodgers denied that campaign and official resources had ever been improperly mixed. The House Ethics Committee did not take any action on the matter.[43]

In 2014, McMorris Rodgers faced Democratic nominee Joe Pakootas, the first Native American candidate to run for Congress in Washington state. McMorris Rodgers defeated Pakootas, 135,470 votes (60.68%) to 87,772 (39.32%).[44]

In 2016, McMorris Rodgers defeated Pakootas again, 192,959 votes (59.64%) to 130,575 (40.36%).[45]

In 2018, McMorris Rodgers faced Democratic nominee Lisa Brown, a former majority leader of the state senate and former chancellor of WSU Spokane. In the August blanket primary, McMorris Rodgers received 49.29% of the vote to Brown’s 45.36%.[46] As of early August, McMorris Rodgers had raised about $3.8 million, and Brown about $2.4 million.[47] McMorris Rodgers and Brown participated in a September 2018 debate. Both said they would oppose any cuts to Medicare or Social Security. Both said they supported the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution. An audience member asked how old the candidates believed the earth is; Rodgers said she believed the account in the Bible, and “Brown said she believed in science, but didn’t provide a specific age”.[48] McMorris defeated Brown with 55% of the vote.[49] Shortly after the election, McMorris Rodgers announced she would stand down from her position as conference chair. Liz Cheney of Wyoming was elected in January 2019 to succeed her.[50]

On February 8, 2024, McMorris Rodgers announced her intent to not run for reelection.[51]

Committee assignments

Caucus memberships

- Congressional Ukraine Caucus[53]

- Republican Main Street Partnership[54]

- Republican Study Committee[55]

- Republican Governance Group[56]

- Rare Disease Caucus[57]

- United States–China Working Group[58]

Interest group ratings

| 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | Selected interest group ratings[59] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 72 | 72 | 84 | 80 | 96 | 96 | American Conservative Union |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Americans for Democratic Action |

| 58 | 62 | 59 | 70 | 61 | 94 | 82 | Club for Growth |

| — | — | — | – | 0 | 0 | 22 | American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees |

| 92 | 92 | 75 | 83 | 90 | 100 | – | Family Research Council |

| — | — | 70 | 76 | 72 | 89 | 84 | National Taxpayers Union |

| 100 | 93 | 83 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 80 | Chamber of Commerce of the United States |

| 0 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 10 | League of Conservation Voters |

Political positions

Health care

McMorris Rodgers opposes the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) and has voted repeatedly to repeal it.[60] In late 2013, she wrote a letter accusing Democrats of being “openly hostile to American values and the Constitution”, and citing the Affordable Care Act and immigration as evidence that Obama “rule[s] by decree”.[61] She blamed the ACA for causing unemployment, and when FactCheck.org reported studies that proved the opposite and asked her office for evidence to support her claims, “McMorris Rodgers’s office got back to us not with an answer, but with a question”.[62]

McMorris Rodgers responded in 2014 to reports that Obama’s program had provided coverage to over 600,000 Washington residents by acknowledging that the law’s framework would probably remain, and that she favored reforms within its structure.[63] In May 2017, she voted in favor of the American Health Care Act, a Republican health-care plan designed to repeal and replace large portions of the ACA. McMorris Rodgers was the only member of Washington’s congressional delegation to vote for the bill, which passed the House by a 217–213 vote.[64] The bill would have eliminated the individual mandate, made large cuts to Medicaid, and allowed insurers to charge higher rates to people with preexisting conditions.[65]

In her 2018 reelection campaign, McMorris Rodgers did not mention the Affordable Care Act.[66]

In 2023, McMorris Rodgers led on a health care bill that aimed to increase transparency in health care pricing and ultimately reduce medical costs. The bipartisan piece of legislation passed the House of Representatives with 320-71[67]

LGBT rights

McMorris Rodgers opposes same-sex marriage, and co-sponsored legislation in 1997 that would ban same-sex marriage in Washington state.[16][68] She co-sponsored the “Marriage Protection Amendment”, an amendment to the Constitution to prohibit same-sex marriage that failed to pass the House in 2006.[69][70]

When a bill was introduced in the state legislature in 2004 that would ban discrimination based on sexual orientation, she voted against it; another bill was introduced in 2006, one year after she entered the House of Representatives. This bill was subsequently passed and signed into law by Governor Christine Gregoire.[5]

During an interview with Nick Gillespie in 2014, McMorris Rodgers stated her belief that marriage should be between a man and a woman and her belief that marriage is a state, not federal, issue.[71][better source needed]

In 2015, McMorris Rodgers voted against upholding Obama’s 2014 executive order banning federal contractors from making hiring decisions that discriminate based on sexual orientation or gender identity.[72]

In 2016, McMorris Rodgers voted against the Maloney Amendment to H.R. 5055 which would prohibit the use of funds for government contractors who discriminate against LGBT employees.[73]

In 2019 and 2021, McMorris Rodgers voted against the Equality Act.[74][75] The bill would prohibit “discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity in areas including public accommodations and facilities, education, federal funding, employment, housing, credit, and the jury system.”[76] She issued a statement claiming that the bill “did not do enough to protect religious liberty.”[77]

In 2022, McMorris Rodgers voted against the Respect for Marriage Act, which would establish federal protections for same-sex and interracial marriages.[78]

Foreign policy

In 2019, McMorris Rodgers was appointed as the Republican Representative to the United Nations General Assembly[79]

In 2020, McMorris Rodgers voted against the National Defense Authorization Act of 2021, which would prevent the president from withdrawing soldiers from Afghanistan without congressional approval.[80]

In 2022 during the prelude to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, McMorris Rodgers stated that she opposed sending American soldiers into Ukraine as a means to deter Russia.[81] McMorris Rodgers was also the only Washington representative to vote against providing $14 billion in humanitarian aid to the government of Ukraine.[82][83] McMorris Rodgers voted in support of sending aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, a bipartisan effort bill aimed at helping U.S. allies[84]

In 2022, McMorris Rodgers helped establish the bipartisan, bicameral Abraham Accords Caucus to support peace in the Middle East.[85]

Marijuana legalization

McMorris Rodgers has expressed support for the enforcement of federal law in states that have legalized marijuana, saying in 2017: “I think about access to marijuana and the other drugs that I believe it leads to. Right now, it’s against the law at the federal level, and until it’s changed at the federal level, I would support [Jeff Sessions‘s] efforts.”[86][87] She later walked back her position, saying that she “lean[s] against” Sessions’s move to rescind the 2013 Cole Memorandum.[88][89] McMorris Rodgers also repeatedly voted against the Rohrabacher–Farr amendment, legislation that limits the enforcement of federal law in states that have legalized medical cannabis.[88][90]

School safety

In 2018, McMorris Rodgers co-sponsored the STOP (Students, Teachers, and Officers Preventing) School Violence Act, which established a federal grant program to “provide $50 million a year for a new federal grant program to train students, teachers, and law enforcement on how to spot and report signs of gun violence”, and authorize $25 million for new physical security measures in schools, such as “new locks, lights, metal detectors, and panic buttons”. A separate spending bill would be required to provide money for the grant program. The House voted 407–10 to approve the bill.[91]

Donald Trump

After Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, McMorris Rodgers became the vice-chair of his transition team. She was widely considered a top choice for Secretary of the Interior.[92] Several papers went so far as to announce she had been chosen.[93][94] Instead, Montana congressman Ryan Zinke was nominated.[95][96][97]

McMorris Rodgers supported Trump’s 2017 executive order to block entry to the United States to citizens of seven predominantly Muslim nations, calling the order necessary “to protect the American people”.[98]

In December 2020, McMorris Rodgers was one of 126 Republican members of the House of Representatives to sign an amicus brief in support of Texas v. Pennsylvania, a lawsuit filed at the United States Supreme Court contesting the results of the 2020 presidential election, in which Joe Biden defeated[99] Trump. The Supreme Court declined to hear the case on the basis that Texas lacked standing under Article III of the Constitution to challenge the results of an election held by another state.[100][101][102]

In January 2021, McMorris Rodgers announced her intention to object to the certification of the Electoral College results in Congress, citing allegations of fraud.[103] She reversed her position after pro-Trump rioters stormed the United States Capitol, and said she would vote to certify Biden’s win.[104]

She was the only member of Washington’s congressional delegation to vote against the impeachment of Donald Trump for his actions stoking the January 6, 2021 assault on the Capitol.[105]

Creationism

McMorris Rodgers rejects the theory of evolution, saying, “the account that I believe is the one in the Bible, that God created the world in seven days.”[106]

Women’s rights

In March 2013, McMorris Rodgers did not support the continuation of the 1994 Violence Against Women Act, but sponsored a clean reauthorization of the bill.[107][108] Ultimately, her bill failed, and the House adopted the Senate version of the bill.[107]

Broadband

In 2021, McMorris Rodgers introduced legislation to prohibit municipalities from building their own broadband networks.[109]

Immigration

McMorris Rodgers voted against the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2020 which authorizes DHS to nearly double the available H-2B visas for the remainder of FY 2020.[110][111]

McMorris Rodgers voted against Consolidated Appropriations Act (H.R. 1158) which effectively prohibits ICE from cooperating with Health and Human Services to detain or remove illegal alien sponsors of unaccompanied alien children (UACs).[112]

Big tech

In July 2021, McMorris Rodgers introduced draft legislation that would allow users of Big Tech platforms to sue companies if they think the companies censored speech protected by the First Amendment.[113]

In 2024, McMorris Rodgers voted in favor of banning TikTok for their ties to the Communist China Party and posing as a national security threat.[114] McMorris Rodgers would lead the Energy and Commerce Committee in a hearing with the TikTok CEO Shou Chew, who testified on TikTok’s consumer privacy and data security practices, the platforms’ impact on kids, and its relationship with the Chinese Communist Party.[115]

Electoral history

| Year | Office | District | Democratic | Republican | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004[116] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Don Barbieri | 40% (121,333) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 60% (179,600) |

| 2006[117] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Peter J. Goldmark | 44% (104,357) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 56% (134,967) |

| 2008[118] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Mark Mays | 35% (112,382) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 65% (211,305) |

| 2010[119] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Daryl Romeyn | 36% (101,146) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 64% (177,235) |

| 2012[120] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Rich Cowan | 38% (117,512) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 62% (191,066) |

| 2014[121] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Joseph (Joe) Pakootas | 39% (87,772) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 61% (135,470) |

| 2016[122] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Joe Pakootas | 40% (130,575) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 60% (192,959) |

| 2018[123] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Lisa Brown | 45% (144,925) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 55% (175,422) |

| 2020[124] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Dave Wilson | 39% (155,737) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 61% (247,815) |

| 2022[125] | U.S. House of Representatives | Washington 5th District | Natasha Hill | 40% (127,585) | Cathy McMorris Rodgers | 60% (188,648) |

Personal life

Cathy McMorris married Brian Rodgers on August 5, 2006, in San Diego. Brian Rodgers is a retired Navy commander and a Spokane native. He is a U.S. Naval Academy graduate, and the son of David H. Rodgers, the mayor of Spokane from 1967 to 1977. In February 2007, she changed her name to Cathy McMorris Rodgers.[126] Having long resided in Stevens County—first Colville, then Deer Park—she now lives in Spokane.

In April 2007, McMorris Rodgers became the first member of Congress in more than a decade to give birth while in office, with the birth of a son.[127] The couple later announced that their child had been diagnosed with Down syndrome.[128] A second child, a daughter, was born in December 2010, and a second daughter in November 2013.[129][130]

According to the Official Congressional Directory, she is a member of Grace Evangelical Free Church in Colville.[131][132]

See also

References

- ^ “After 20 years at the Capitol, Cathy McMorris Rodgers leaves behind a changed Congress: ‘When she speaks, people listen’“. Spokesman.com. December 30, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2025.

- ^ “Timeline: Cathy McMorris Rodgers through the years”. Spokesman.com. December 29, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2025.

- ^ Alfaro, Mariana (February 8, 2024). “Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers won’t seek reelection to House”. The Washington Post.

- ^ “2024 Washington Election Results”. Associated Press News.

- ^ a b c d e Graman, Kevin (October 17, 2004). “McMorris has defended timber, mining industries and supported conservative line on social issues”. The Spokesman-Review. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ “Vesta Delaney Obituary”. ObitsforLife.com. Bollman Funeral Home. 2013. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- ^ Mimms, Sarah (September 19, 2014). “Is Cathy McMorris Rodgers More Than a Token?”. The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ “10 things to know about Cathy McMorris Rodgers”. Politico. January 27, 2014. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ a b “Representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers”. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ^ “Can Cathy McMorris Rodgers resurrect compassionate conservatism?”. The Washington Post. January 28, 2014. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Bartlett, Thomas (March 24, 2006). “A College That’s Strictly Different”. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ “Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.)”. Roll Call. 2014. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ a b “Youngest Representative in State of Disbelief”. The Wenatchee World. January 11, 1994. p. 14.

- ^ a b “Sen. Bob Morton announces retirement”. gazette-tribune.com. December 5, 2012. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ “Election Results”. The Seattle Times. September 21, 1994. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ a b “Gay-rights Rally Opposes Bills to Ban Same-sex Marriage”. the Spokesman-Review. February 4, 1997. p. B6. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ “HB 1130 – 1997-98: Re-affirming and protecting the institution of marriage”. Washington State Legislature. June 11, 1998. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Galloway, Angela (April 6, 2001). “Effort to excise ‘Oriental’ from state documents may be revived”. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on July 22, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ “The Times Endorses McMorris in the 5th” (editorial). Seattle Post-Intelligencer. October 22, 2004. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ “Biographical Information – McMorris Rodgers, Cathy”. Congressional Biographical Directory. United States Congress. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ^ “Legislative leaders’ changing of the guard”. The Seattle Times. January 11, 2004. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ “Women in Business Spotlight on Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, House Republican Conference Chair”. U.S. Chamber of Commerce. December 10, 2012. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ “Members”. Republican Mains Street Partnership. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ “Members”. Congressional Constitution Caucus. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ “Members”. Congressional Western Caucus. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ “2006 General Election Results”. Ballotpedia. May 9, 2007. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ^ Postman, David (January 22, 2007). “McMorris to head women’s caucus”. Postman on Politics. Archived from the original on February 1, 2007. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ^ “Congressional District 5 – U.S. Representative – County Results”. Washington Secretary of State. 2008. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Snell, Kelsey (July 6, 2018). “Highest-Ranking Republican Woman Faces Tough Re-Election”. NPR.org. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ “Vice Chair accomplishments”. mcmorris.house.gov/. 2012. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ “Jenkins Elected as House Republican Conference Vice Chair”. lynnjenkins.house.gov. November 14, 2012. Archived from the original on September 23, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ “Washington U.S. House #5”. NBC. 2010. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ “Cathy McMorris Rodgers”. Open Secrets. 2014. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Bendavid, Naftali (November 14, 2012). “McMorris Rodgers Gets GOP House Post”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ “Congressional District 5 – U.S. Representative – County Results”. Washington Secretary of State. 2012. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Hill, Kip, “Bill eases regulations on hydropower projects” Archived February 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Spokesman-Review, August 16, 2013.

- ^ Cowan, Richard (January 23, 2014). “Republican congresswoman to rebut Obama State of Union speech”. Reuters. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ Michael, O’Brien (January 23, 2014). “GOP taps top-ranking woman to deliver SOTU response”. NBC News. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ “Republicans pitch Washington state Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers as a rising star”. The Miami Herald. January 28, 2014. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Ostermeier, Eric (January 27, 2014). “A Brief History of Republican SOTU Responses”. Smart Politics. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ “Ros-Lehtinen to deliver Spanish SOTU response”. The Hill. January 28, 2014. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Sherman, Jake (February 6, 2014). “GOP Conference chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers faces possible ethics inquiry”. Politico. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ a b “GOP consultant admits lying to ethics investigators”. USA Today. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ^ “Congressional District 5 – U.S. Representative – County Results”. Washington Secretary of State. 2012. Archived from the original on November 18, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ “Congressional District 5”. results.vote.wa.gov. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016.

- ^ “August 7, 2018 Primary Results – Congressional District 5 – U.S. Representative”. results.vote.wa.gov. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ “Washington state primary election: GOP’s McMorris Rodgers, Herrera Beutler face tight races in November”. The Seattle Times. August 7, 2018. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ^ “US House Candidates Debate Gun Control, Age of Earth”. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ “Washington Election Results: Fifth House District”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ Killough, Ashley (November 9, 2018). “McMorris Rodgers won’t run for re-election as GOP conference chair”. CNN. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- ^ Talbot, Haley (February 8, 2024). “Cathy McMorris Rodgers won’t seek reelection, the latest establishment Republican planning to leave Congress”. CNN via MSN. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ “Meet the Republican Leader – Energy and Commerce Committee”. Energy and Commerce Committee. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ “Members”. Congressional Ukraine Caucus. Retrieved November 5, 2025.

- ^ “MEMBERS”. RMSP. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ “Member List”. Republican Study Committee. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ “The Republican Governance Group / Tuesday Group PAC (RG2 PAC)”. Republican Governance. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ “Rare Disease Congressional Caucus”. Every Life Foundation for Rare Diseases. Retrieved December 13, 2024.

- ^ “Our Mission”. U.S.-China Working Group. Retrieved February 27, 2025.

- ^ “Cathy McMorris Rodgers”. votesmart.org. 2014. Archived from the original on March 22, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Song, Kyung M. (January 23, 2014). “Spokane’s McMorris Rodgers to give GOP response to Obama address”. The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ “Democrats ‘openly hostile to American values’, say Rep. McMorris Rodgers”. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. December 16, 2013. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ “Is Obamacare Causing Health Care Layoffs?”. FactCheck.org. January 17, 2014. Archived from the original on January 31, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Hill, Kip (April 25, 2014). “McMorris Rodgers says ACA likely to stay”. The Spokesman-Review. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ Camden, Jim (May 4, 2017). “Washington leaders react to House vote on health care”. The Spokesman-Review. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Morgan, David; Abutaleb, Yasmeen. “U.S. House Passes Republican Health Bill, a Step toward Obamacare Repeal”. Scientific American. Reuters. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Resnick, Gideon (September 21, 2018). “Suddenly, Vulnerable House Republicans No Longer Bash Obamacare on Their Websites”. The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ “House passes McMorris Rodgers’ bill aimed at lowering health care costs, increasing transparency | The Spokesman-Review”. www.spokesman.com. December 11, 2023.

- ^ “HB 1130 – 1997-98: Reaffirming and protecting the institution of marriage”. Washington State Legislature. June 11, 1998. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ “H.J.Res.88 – Marriage Protection Amendment: 109th Congress (2005–2006)”. United States House of Representatives. July 18, 2006. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Tashman, Brian (August 6, 2014). “Cathy McMorris Rodgers Denies That Steve King — Who Wrote GOP Immigration Policy — Represents Republicans On Immigration”. Right Wing Watch. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ “Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers on Gay Marriage, Tech, and the GOP”. ReasonTV on YouTube. August 5, 2014. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ upholding President Barack Obama’s 2014 executive order banning federal contractors from making hiring decisions that discriminate based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

- ^ “H.Amdt. 1128 (Maloney) to H.R. 5055: Amendment, as offered, prohibits … — House Vote #258 — May 25, 2016”. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Washington, U. S. Capitol Room H154; p:225-7000, DC 20515-6601 (May 17, 2019). “Roll Call 217 Roll Call 217, Bill Number: H. R. 5, 116th Congress, 1st Session”. Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Washington, U. S. Capitol Room H154; p:225-7000, DC 20515-6601 (February 25, 2021). “Roll Call 39 Roll Call 39, Bill Number: H. R. 5, 117th Congress, 1st Session”. Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on January 7, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ “H.R.5 – 116th Congress (2019-2020): Equality Act”. www.congress.gov. May 20, 2019. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ McMorris Rodgers, Cathy (May 17, 2019). “McMorris Rodgers Statement on the Equality Act”. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ “On Passage – H.R.8404: To repeal the Defense of Marriage Act and…” ProPublica. July 19, 2022. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ “McMorris Rodgers Appointed as Republican Representative to the United Nations General Assembly”. Cathy McMorris Rodgers.

- ^ “H.R. 6395: William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act … — House Vote #152 — Jul 21, 2020”. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ “It’s time to ‘flip the switch,’ say ‘yes’ to American energy: Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers”. February 17, 2022. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Solender, Andrew (March 11, 2022). “Congress passes $1.5 trillion bill to fund government”. Axios. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ “On Concurring in Senate Amdt with… – H.R.2471: To measure the progress of post-disaster”. August 12, 2015. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Edmondson, Catie; Gómez, Martín González; Guo, Kayla; Jimison, Robert; Sun, Albert; Yourish, Karen (April 20, 2024). “How the House Voted on Foreign Aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan”. The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ “McMorris Rodgers Announces Bipartisan, Bicameral Abraham Accords Caucus to Support Peace in the Middle East”. Cathy McMorris Rodgers.

- ^ Walters, Daniel (January 11, 2018). “Sessions’ marijuana actions put GOP politicians like Cathy McMorris Rodgers in a tough spot”. The Inlander. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Gardner, Elena (August 11, 2017). “McMorris Rodgers explains stance on legal usage of marijuana at town hall”. KXLY. Archived from the original on June 7, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Angell, Tom (September 3, 2018). “A Top House Republican Questions Jeff Sessions’s Anti-Marijuana Moves”. Marijuana Moment. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Hill, Kip (September 2, 2018). “Where they stand: Cathy McMorris Rodgers, Lisa Brown give stances on marijuana, opioid addiction treatment and drugs”. The Spokesman-Review. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Ferner, Matt (June 16, 2014). “New Ad Targets GOP Congresswoman Over Opposition To Medical Marijuana”. Huffington Post. Archived from the original on June 7, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Zanona, Melanie (March 14, 2018). “House passes school safety bill amid gun protests”. The Hill. Archived from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Mapes, Lynda (December 9, 2016). “Cathy McMorris Rodgers reportedly top contender to head Interior”. The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on February 4, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Gibson, Ginger; Volcovici, Valerie (December 9, 2016). “Oil drilling advocate to be Trump pick for Interior Department”. Reuters. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ “Climate skeptic Cathy McMorris Rodgers set for Department of Interior post”. The Guardian. December 9, 2016. Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Davenport, Coral (December 13, 2016). “Trump Is Said to Offer Interior Job to Ryan Zinke, Montana Lawmaker”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet (December 13, 2016). “Trump taps Montana congressman Ryan Zinke as interior secretary”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Yardley, William (December 15, 2016). “Ryan Zinke, Trump’s pick as Interior secretary, is all over the map on some key issues”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 4, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Blake, Aaron (January 29, 2017). “Coffman, Gardner join Republicans against President Trump’s travel ban; here’s where the rest stand”. The Denver Post. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Blood, Michael R.; Riccardi, Nicholas (December 5, 2020). “Biden officially secures enough electors to become president”. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (December 11, 2020). “Supreme Court Rejects Texas Suit Seeking to Subvert Election”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ “Order in Pending Case” (PDF). Supreme Court of the United States. December 11, 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ Diaz, Daniella. “Brief from 126 Republicans supporting Texas lawsuit in Supreme Court”. CNN. Archived from the original on December 12, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ “McMorris Rodgers to object to Electoral College count”. AP NEWS. January 6, 2021. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ “WATCH: Following protests McMorris Rodgers flips saying she will now uphold Electoral College results”. KHQ Right Now. January 6, 2021. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ “U.S. Rep. McMorris Rodgers won’t seek reelection”. The Seattle Times. February 8, 2024.

- ^ “From Kettle Falls to the Capitol, Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers used conservative bona fides to rise through ranks | The Spokesman-Review”. www.spokesman.com. October 10, 2018. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b “Washington’s McMorris Rodgers will respond to Obama”. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. January 23, 2014. Archived from the original on January 30, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Bendery, Jennifer (January 29, 2013). “Violence Against Women Act Senate Vote Next Week”. Elect Women. electwomen.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Brodkin, Jon (February 18, 2021). “House Republicans propose nationwide ban on municipal broadband networks”. Ars Technica. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ “Text – H.R.1865 – 116th Congress (2019-2020): Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 | Congress.gov | Library of Congress”. Congress.gov. December 20, 2019. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ “Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives”. clerk.house.gov. December 17, 2019. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ “H.R. 1158: DHS Cyber Hunt and Incident Response Teams Act … — House Vote #690 — Dec 17, 2019”. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ “Section 230: GOP congresswoman urges more free speech on Big Tech platforms”. Fox Business. December 2, 2021. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ “Cathy McMorris Rodgers explains why she voted in favor of House bill that could ban TikTok”. krem.com. March 13, 2024.

- ^ “Energy and Commerce to Bring TikTok CEO Before Committee to Testify”. House Committee on Energy and Commerce.

- ^ “November 2004 General”. Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ “November 2006 General”. Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ “2008 U.S. Congressional District 5 – Representative”. Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ “2010 Congressional District 5 – U.S. Representative”. Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ “November 6, 2012 General Election”. Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ “November 4, 2014 General Election”. Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on September 6, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ “November 8, 2016 General Election”. Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ “November 6, 2018 General Election”. Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ Wyman, Kim (December 1, 2020). “Canvass of the Returns of the General Election Held on November 3, 2020” (PDF). Secretary of State of Washington. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2025. Retrieved July 15, 2025.

- ^ Hobbs, Steve (December 7, 2022). “Canvass of the Returns of the General Election Held on November 8, 2022” (PDF). Secretary of State of Washington. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 22, 2025. Retrieved July 15, 2025.

- ^ “Congresswoman changes name to McMorris Rodgers, WA”. The Associated Press News Service. February 1, 2007.

- ^ Cannata, Amy (April 30, 2007). “It’s A Boy”. Spokesman Review. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ^ McMorris Rodgers, Cathy (2008). “My Down Syndrome Story”. Mcmorris.house.gov. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Barone, Michael; McCutcheon, Chuck (2011). “Washington/Fifth District”. The Almanac of American Politics (2012 ed.). University of Chicago Press, National Journal Group, Inc. pp. 1716–1718. ISBN 978-0-226-03808-7.

- ^ Bobic, Igor (November 25, 2013). “Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers Gives Birth To Daughter”. Talking Points Memo. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ “FIFTH DISTRICT” (PDF). Official Congressional Directory. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ McMorris Rodgers, Cathy (2010). “McMorris Rodgers’ Pastor Tim Goble of Colville Delivers Opening Prayer for Congress”. Mcmorris.house.gov. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

External links

- Congresswoman Cathy McMorris Rodgers official U.S. House website

- Cathy McMorris Rodgers for Congress

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Legislation sponsored at the Library of Congress

- Profile at Vote Smart